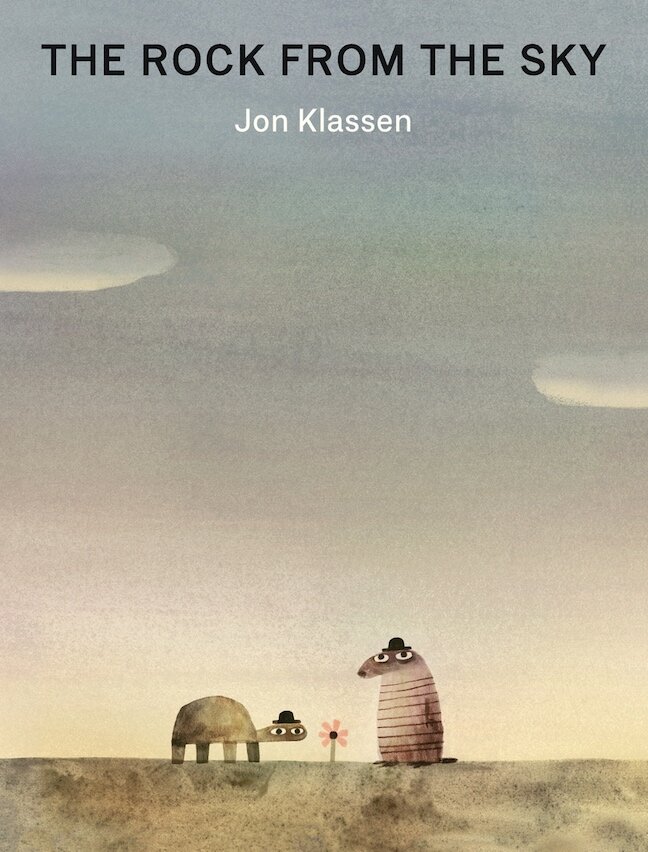

An Interview with Jon Klassen

Jon Klassen—Photo by Autumn Le' Brannon

October 17, 2014

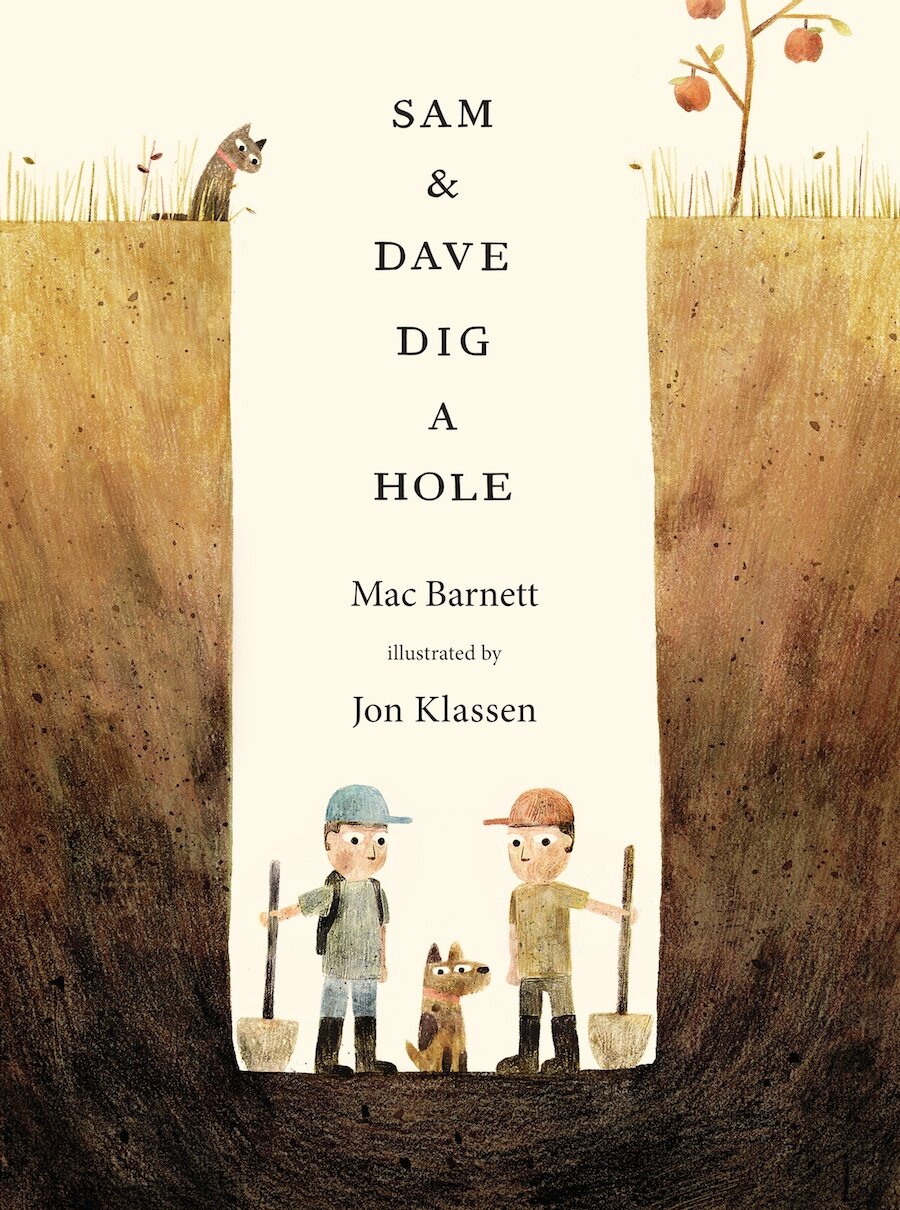

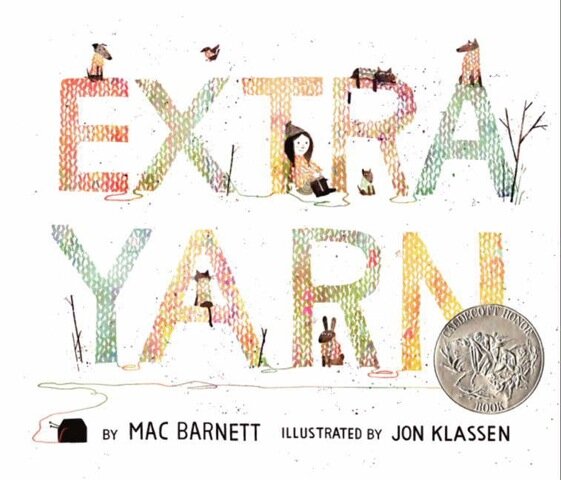

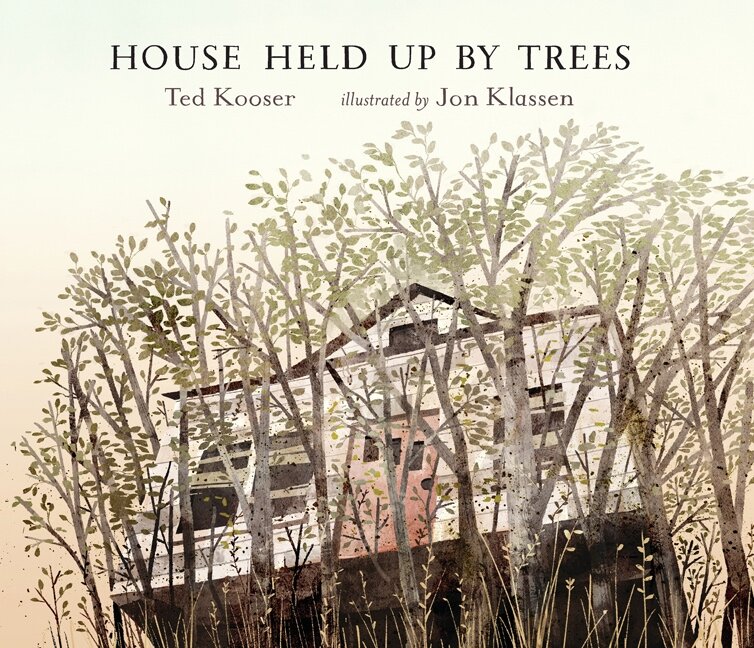

We interviewed Jon Klassen, New York Times best selling illustrator and author of children's books, including the 2013 Caldecott Medal winner, This Is Not My Hat, and I Want My Hat Back, New York Times Best Illustrated Book of 2011 and 2010 Canadian Governor General's Award winner. He also illustrated Extra Yarn, a 2013 Caldecott Honor book, and 2015 Caldecott Honor book, Sam & Dave Dig a Hole, both by Mac Barnett.

You and Mac Barnett have collaborated on two books, Extra Yarn and Sam & Dave Dig a Hole. We love the trailer for Sam & Dave Dig a Hole. Did you come up with the idea for this book together?

Yes, we did think of it together. Mac was in town and he was talking about what you could do with kids digging a hole and missing things. I really liked the idea. Book illustration for me is figuring out the format and how to get the parts to work together – making sure that the text isn’t just squished on the page, or that the illustration is just rubbed away to make room for the text to be inserted.

You've said that you keep coming back to the idea of a search for something, where you end up hitting rock-bottom. That so perfectly describes Sam & Dave Dig a Hole.

Yes, a lot of the stories I come up with do involve a search, until I reach a point where I wonder how am I going to solve this. It's an interesting point in the story structure. Sam & Dave is like that. What drives a large part of the story is how is it going to end, how is it going to solve itself. That was a big part of writing and illustrating it. There are things that feel right for the premise and things that feel like you might be taking it in the wrong direction. That process is new every time. There's no real recipe for it. You're just following what it is that got you excited about it in the first place. In this book, it was especially tricky because we had dug the hole and we couldn't get out! So we're at the bottom of the page and now what? Of course it wasn’t written as haphazardly as that. Mac always has an ending in mind, but we were trying to figure out how to make it clear and direct and also as dreamy as we wanted.

Cover from Sam & Dave Dig a Hole, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Jon Klassen

Would you say this story is left open-ended?

Toward the end the text just says, “They landed in some soft dirt.” A lot of the objects look the same, but there are small differences and we don't say it in the text. We leave it to the viewer to realize that this is not home. But the boys don't notice. They’re thinking, “Wow, that was pretty spectacular! We've been looking for something interesting to happen all day and that was certainly it.” So they walk back inside for milk and cookies and that is the end. But the dog is given one extra page to take a look around and realize that they are not home. The boys are already in the house, looking at who knows what, because they are not home either. So it is left open, but it also feels complete.

An interesting thing it brings up is that if the text doesn't state something, then the readers have to look at the pictures. On a tour, I was showing the book to some kids, and when the boys seemed to be back home, the kids listening to the story saw the differences and they were confused. Once we explain what has happened, it is a reassurance that they were right all along. This was not completely on the level. Their first impulse was correct. I think that's a very reassuring thing. You can validate that insecurity they have when they see that final page. And they can back it up because it turns out that things aren't quite right.

And that allows kids to be proud of a sixth sense they have.

Yes, exactly. If they're being read to by an adult, I feel that the pictures are the kids’ territory. So if the pictures give out some information that the text doesn’t, there's a secret from the person reading it or maybe even from the person who wrote it. Kids learn to read more critically; they realize these pictures have a reason. They are not just there to entertain us while all the important text is happening.

With your stories’ intentionally ambiguous endings, do you feel that it allows your audience to find their own way?

Yes. It's a fine line though, because you don't want to come off as someone who doesn't feel like giving them all the answers. You don't want to seem lazy or arty, as if to say, “You guys figure it out! I don't know what's going on.” You have to be very specific about what it is that you want to say.

It must be interesting to hear some of those reactions to your stories.

It's great! Even in this book, Sam and Dave's relationship can be seen in different ways. They seem to be very stoic little guys but it is how you interpret them: Is one guy more right than the other? We know what we think about these guys, but I'm always surprised to find that people have opinions of characters and that it can change drastically from person to person. It doesn't mean they misunderstood the story. It means they brought other experiences to an event in the book that reminded them of something. Once you've laid out simply what happens in the book, then it's off to the races. They can see whatever they want. It's really a neat back-and-forth.

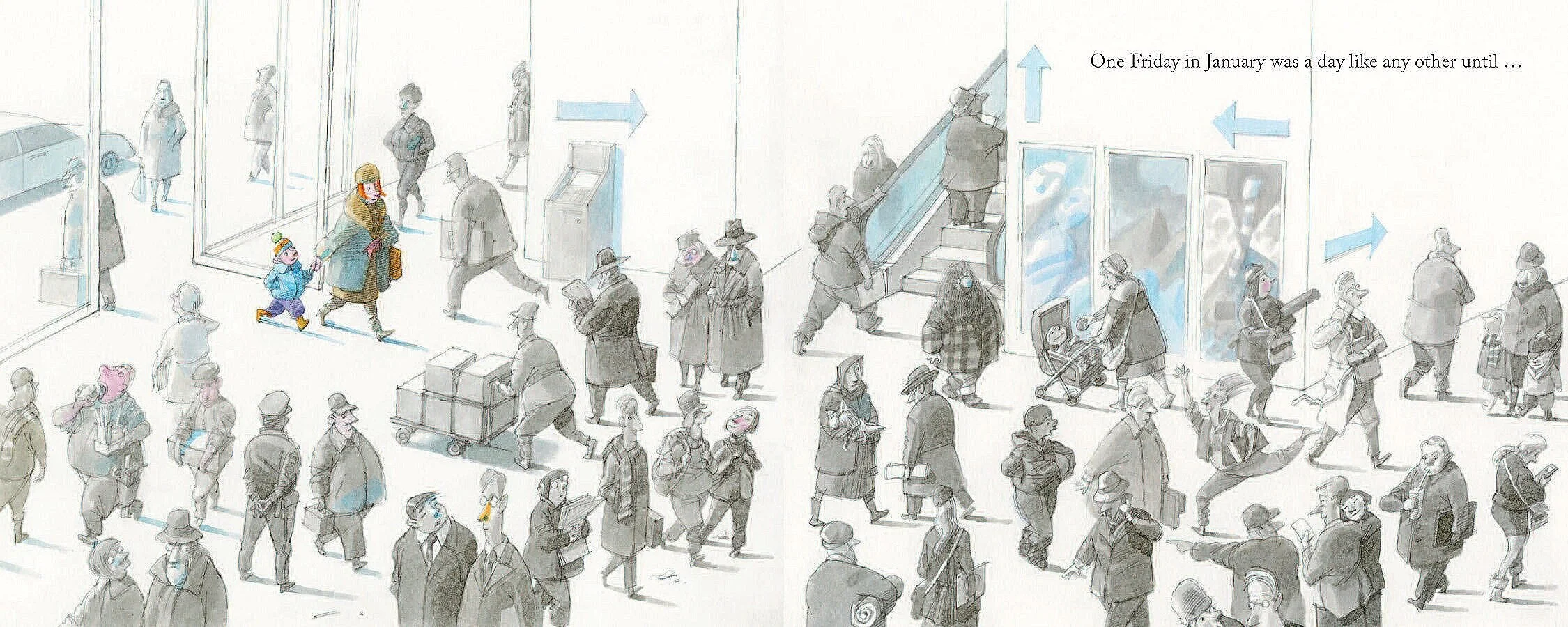

Interior spread from Sam & Dave Dig a Hole, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Jon Klassen

It’s been said that your children's books tend to be edgier than most; you avoid wrapping things up neatly with a bow. What’s your response to that impression of your work?

I never want to promote edgy things just for the sake of it. I think there's as much danger in that as going the other way and being too sweet or just too convenient. When the premise suggests that this can end more ambiguously, and if there's more to be gained there, it should be allowed to do that. I think kids are fine with that. They can’t necessarily tell you that they want sweeter things or edgier things. They just want a good story to be told as well as it can be told. They want to be entertained in a very uncomplicated way.

You could traumatize an audience with the wrong decisions. But I don't think that's inherent in scary stories. I loved being scared as a little kid—through books particularly though. And I think that’s an important difference. With movies and television, it was too traumatic for me. I find it overwhelming when things are gratuitously violent. But with books, you can take it as it comes, trust that you can turn the page when you're ready. Children's books—they’re supposed to be simple, and they are. A great challenge is to build the suspense with simple elements. You can condense everything about a scary story and bring it down to the language of the kid. They know that this is something for them and that they've not wandered into someplace that they're not ready for. It's amazing and it's so much fun.

You can deliver bad messages in a very sweet book, too. There's plenty of misguided stuff that sounds just as sweet as can be. These things come in many forms.

There's some sweet stuff that is actually very scary!

Yes. Exactly! Once kids get used to that, it’s much more dangerous than them getting used to the scary stuff.

Both of us at Art of the Picture Book have been dog owners, and we feel you really nail it with the eyes on your animal characters–especially in the way their eyes move, while their expression remains the same. What's behind that subtle approach to character?

Interior spread from This Is Not My Hat, Jon Klassen

I grew up with dogs. We have a cat now. You get used to animals showing how they feel. You can't help but look for human emotions in them. They don't have a lot of ways of showing those things, so you get attuned to smaller movements. But it's also fun as an illustrator to draw the same thing five times and then, when you change it just once, it becomes meaningful. It doesn't have to look very complicated. It's a symbol of how they're feeling.

You can't draw a frustrated dog. When the situation is frustrating, he should be frustrated. You can give just the slightest indication, like if he was frustrated, he’d be looking at us by now.

In Sam & Dave Dig a Hole, the dog has been looking down at the diamonds the boys have been missing in the dirt throughout the entire book. And then at one point they miss the largest diamond in the book—it’s almost two pages across. The dog has just had it, he’s so frustrated that they keep missing these things, that he doesn't even bother to look at the diamond anymore. He’s looking at us for the first time, like in a comedy show, where they break to look at the camera, as if to say, “Can you believe this?”

It's as if you are making a film with really bad actors. They can't stop looking at the camera or they can't help but comment on the story outside of their place in it. With this book, that was the moment to do it. In picture books, the images are so spare that there are usually some opportunities to do that.

I don't have any trouble with the idea of making up a character. But it seems so pompous to say, "I've made up this guy and I know everything about him.” You can't know a person like that. We’ve got these two cute kids and there's the dog. But they also have outside lives that we don't know or understand. We get them to say our very simple lines and make them do their actions. I can think of characters like that. Their actions are very stiff. There's one point when the boys begin to split up and Dave puts his hand on Sam’s shoulder. It's a theatrical stagey action. It's not a private moment, because we can see them making this pose, but it also is an emotional moment. Like in a play, you can find yourself lost in the emotions. But at the same time, the actors are shouting the whole time. You can hear them from way in the back. And they're always facing the audience, favoring the theater’s audience. So it looks fake and you know it's fake, but you are still lost in what's going on. And I love that. When you can be artificial with the audience and you've done everything you can to convince them of that, but they can't help but get into your story. They get past all of that.

Interior spread from Sam & Dave Dig a Hole, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Jon Klassen

They're still being touched by it despite all the artifice.

Yes, exactly. And there is artifice in illustration. You are up against your own skills as an artist. You can only play at making a fake tree. No one thinks it's a real tree, but they know it’s supposed to be a tree. That's way more fun than actually trying to draw a tree.

Although your landscapes are often quite spartan and they make no attempt to be realistic, they do stand in for exactly what you need for your story.

Right, they’re just symbols. They can get more complicated the better you get as an illustrator, depending on what the story needs them to be. The audience is always looking for symbols. You can have a beautiful illustration, but if it doesn't have the symbols that simply communicate what you need to communicate, then they’ll get lost. It’s the same with film. You can have a beautiful sequence of shots, but if it's not organized clearly, you get lost and the story’s gone. You've lost your audience, no matter how well you've done visually. It always has to have the idea behind it first.

Interior page from Extra Yarn, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Jon Klassen

You've said that illustration for you is a little scary because, unlike with animation, your drawing is not one of thousands. Each one stands on its own. The reader can hold onto the page for as long as they like. You no longer have that sense that it's going to be gone in a second. Every line and every bit matters.

Yes, at first it is really scary, because you're used to the safety of these drawings going by relatively quickly. Once you watch a film you've worked on, you realize how quickly this work goes by and it loosens you up. It’s just a different language. It's all moving instead of holding still.

With books, at first you think, “How am I supposed to live up to the idea that this is just sitting there on the page?” It's the only image that the readers will get to represent this particular moment. But then you get used to paper and leaving something behind on the page.

With animation, you fill up the frame all the time because you want it to be immersive. There's the implication of a much broader world off the frame all the time.

But with books, it's the opposite. You want it to feel like you thought of this picture specifically for this page. They are not just getting the book version of this story. This is the only story and this is the only way you're ever going to hear it. This is the only way it makes any sense, in this particular form. You choose your trim size for that, you choose your pages for that, and you know them going in. You don't plan an illustration that wouldn't work with that. You know you have complete control over it inside those parameters.

It's such a huge honor to get to do this. You would never move if you got too nervous about the permanence of it. When you go back to your old books, you remember that these were once perfect little diamonds, and now you see all the small mistakes. But they don't matter. You've done the story’s best job before the illustrations even got there.

Cover of I Want My Hat Back, Jon Klassen

When you do a layout of a book, do you create several rough drafts?

It depends on whether I'm writing it or not. If I'm writing it, I have to be very specific with myself because the whole thing is done at once. You're thinking of an idea because it's a 40-page idea. You're not thinking of a 60-page idea and trying to squish it into 40. You make decisions based on if it’s wide, tall, or square. You think of those rules first and then make the story fit. You go back and forth. You have the power to do that because you’re writing it yourself.

Working with writer Mac Barnett it's different because we're friends and we talk all the time, and so it’s a bit more malleable. But usually when the text comes, you want to figure it out. It's a known quantity. You don't have the ability to change things inside that story. And you don't even want it. It is nice to have that huge head start. There are problems to solve, versus this big vat of nothingness!

Interior page from Extra Yarn, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Jon Klassen

I am lucky to work with some great authors. My favorite part of illustrating someone else's text is where I am directing. Someone else wrote the script and now I get to figure how to pace it and make it land over the pages. It's not even about drawing; it's about something else completely. With old books, like those P.D. Eastman ones, the stories made almost no sense. They turn and do weird things, but at the end of the book you feel the book has ended. It has landed and you're satisfied. It's such a mystery every time. It's the best thing when you can get it working. There's no plan for it, it just happens. It's why a kid wants to read a book over and over again. Because it just lands.

Is that the part you really enjoy—the problem solving? You’ve said that you don't want just to sit and “express yourself” through your drawing.

Yes, it’s interesting, because it does get so emotional anyway. You can find yourself inside that problem solving. What you are doing is measuring your reactions to things. If you feel especially sad at a certain point, you think, "Why am I feeling sad about this?” You have to open the hood a little bit. You don't want to, because it's such a nice little mystery. But when you’re the person who makes these things, you have to understand how to take your own temperature. Once you've found that moment, you want to support it, give it all the juice you can. That's about as personal as it gets.

I like stories. I like reasons for things. It’s the same reason I like graphic design and illustration. I begin to get interested when there is a story to tell or a point to be made. If it's just drawing, I never really got much out of that. I never had the confidence in my drawing to think that it could stand by itself. For me, I always liked the trick of having something else represented.

In high school, we read Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. After, the teacher said, “What do you think Hemingway was doing?” The subsequent discussion changed my viewpoint. That these books, and that art, in general, could be about something beyond what it was literally describing. The book wasn't about the characters and it wasn't about the plot; the book was his best way of describing something larger. It showed me the intellectual side to creative work. It wasn't just self-indulgence; you could be connected to people through it.

How do you come up with ideas for your books? What is your jumping off point?

It's just born of fear—of creating. It's laying down rules as soon as you can to get out of the abyss of what the thing could be and to get it to be something that you can play with. For me, every time, it's been like a trick. It's been a way of avoiding something I don't want to do. And the solution to that avoidance lends itself to a story. Like in Sam & Dave, you wouldn't really want to show the mechanics of how to dig a very deep hole, and how to get rid of all that dirt. There's just a hole where there wasn't one before and you don’t deal with all these technical things. The story wouldn't be possible if you got more involved. And as long as the rest of the audience is okay with avoiding those things too, then you're good to go.

Interior spread from I Want My Hat Back, Jon Klassen

Writing, for me, has always been the same thing. I like writing books in dialogue because I don't have any idea what narration sounds like coming from me yet. It wasn't really a creative choice to say this story would be better this way. It was me saying, "I don't know how to write any other way." Hopefully no one notices the things you're leaving out. The whole story is working and it feels complete and the idea is fitting and doing its thing. You said, “I don't want to do that and I don't want to do that. And so what do I have left? I have this left.” You never know what you want, you just know what you don't want. It's a sculpting process. It's a big chunk of marble and it's just terrifying. Anything could be in there. You just keep making these small notches until you've got the shape—where everything that you didn't want is gone.

That appears to be working beautifully for you. It seems like you follow the trail and when you get to the end, you succeed at landing.

It does appear to work, although there's no way to repeat it. It only works for the one thing. There’s nothing to be gained for the rest of the books. You can’t say, “Well, this worked for the other one, so let's do that again.” The most interesting part about stories is that they’re local. They work on their own. They work specifically to themselves. But at the same time, as soon as you want to start a new one, you haven't learned much that you can apply to start another one. So it keeps things interesting. It also keeps things terrifying!

Evidently terrifying may be good!

It is good. Because as soon as you're not terrified, you're bored. And that's way worse.

With animation and illustration techniques having so much overlap today, you’ve said that it allows for fresh work to be created. And with new technological advancements, creators can now go back and forth between different forms. What do you see coming from this closer relationship?

I think there's a lot to be gained by going between different forms. It's like learning different languages. If you only speak one language your whole life, your idea of language as a concept is limited. When you begin to learn the rules of how languages in general are put together, you understand your own better. It's something you can play with and you understand the tools, the levers, and the strings. Forms are like that also. If you're toggling between film and books, there are different rules that govern them. You almost never have an idea just for a story, you have an idea for a book or you have an idea for a film— because you’re thinking of the format first. You’re thinking of 30 pages and a gutter, or you’re thinking of a five-minute short. And a lot of these things can’t be brought over. You don't want necessarily for that book to be made into a film, because you wanted it to have found its form perfectly.

Cover of This Is Not My Hat, Jon Klassen

Now the technology is different. These tools are much more condensed and accessible. If you get back into books after two years of making films, you're seeing the possibility in books differently. You're so excited to be back where things hold still. Or the reverse, you’re back in film because you've been in books for a while and you’re glad to have sound again. You get fresher because you have it as a new way to tell the story.

Now these communities are more blurred. You find people that are doing both books and film. People are jumping back and forth. It’s really neat right now, with all sorts of cross-pollination going on.

Are you still doing animation?

I do a little bit of it. I don’t get into larger projects much anymore. With animation, a project can take three or four years to complete. With books, it took about eight months to make a book and I couldn’t believe it—to be able to get the story you wanted in that short amount of time.

With short animation though, for tablets and mobile apps, I’ve been doing some direction and design. It is so much fun to work in a group again—to hang out and make something collaboratively with 10 or 20 people—that you never would have done by yourself.

But the books are just everything. As long as I can make books, I’m going to be doing it.

Do you keep a sketchbook of ideas and drawings of things you see or from your imagination?

Not really. I’ve always been really bad at it. When I went to school for animation, the animators drew as a muscular reaction to things. They just loved it. These kids kept beautiful sketchbooks. They would sit on the subway with their books out, drawing some weird-looking guy on the train. It’s just not what I do. I would always end up writing in my sketchbook or making doodles. More and more, if I draw without a story it’s because I want to research a technique.

But with book illustration, things get better the more mediums you know how to work with. If I decide the next story’s going to be best told with pastels, then I’ll do some pictures with pastels, that don’t necessarily have a story behind them. But I don’t keep a sketchbook of that. There are drawings everywhere and they’re very disorganized. As long as I get them into the computer, then I’m not too romantic about what the physical pieces were. They always end up under the couch or something. It’s not good.

Interior spread from I Want My Hat Back, Jon Klassen

I always felt terrible that I didn’t keep a sketchbook. I still do. I like to hear about someone else that didn’t keep one and they managed to find their interests in other ways. I like to find those kids and tell them, “Hey, you don’t have to keep this beautiful Leonardo da Vinci style sketchbook. If that’s not your impulse, then don’t force it. There are other ways.”

So you put your drawings into Photoshop and then piece together what you’ve drawn?

Yes. I really like working that way because it takes the pressure off the drawings themselves. You can loosen up. For every dog that made it into Sam & Dave, there’s probably 10 dogs that didn’t. You do a bunch of dogs and decide that you like “Dog Number Four.” That’s the guy that will make it onto the page. You can experiment a little and you’re not so pressured to like the one piece. If you spill coffee on it, then you haven’t lost it. I think it’s becoming a more popular way to work. Computers are so great at compiling things. You can do something in charcoal and scan it into Photoshop and you can just blast it with contrast and you get this whole new picture that you can’t believe you had anything to do with. It’s a fun way of working. It’s safe. You can take all sorts of chances because the computer gives you a big safety net.

And you like to look at old photos . . .

I love photography in general. I think photography has a lot more to say than illustration does in terms of the things I like to make. Photography and illustration have such an interesting relationship. If you’re given a story as an illustrator, that is a known quantity and you have to find what you have to say about that story; you have to find out where you stand in relationship to that story.

Photographers have an object or a scene and where they’re standing is everything. Every small decision they’re making is from their instincts. With a great photograph, it’s really hard to say why it’s a great picture. But it is where they chose to stand on it. It’s fascinating. I love it. Good photographers are interesting to me because they are so reactionary that they can’t explain the why of what they do. It’s just a gut reaction.

Also, where photography is now technologically—and it’s the same as with illustration— all these cheats are available. It’s like anybody can take a good photo, where the color’s right and the focus. It’s beside the point now. Everybody is a photographer. So now it’s about where you’re standing again. It’s not about how beautiful the photo is or if you can apply a filter to it properly because anybody can do that.

I think it should be the same with illustration. Lots of people can draw really beautifully or they can make something pretty with Photoshop. But where are you standing? What do you have to say?

So what choices are you making?

Exactly that. I taught a class at Cal Arts last year and that was pretty much the theme of it. These kids are all so good at drawing when they get into this school. But I would ask, “Why are you drawing what you’re drawing? Think about it. Every decision you make is communicating something.”

Interior spread from This Is Not My Hat, Jon Klassen

How do you do research for a book?

Some people make a wall of inspiration around what the book is about. But I like the idea that your impressions of something are just as valid as any research you would do.

For Sam & Dave, I was really interested in the artist David Hockney. He has a great series of colored pencil drawings: beautiful, soft, with just the right moments of punchy color. Amazing work. I thought color pencil would be a good fit for this story because it’s all about dirt and I wanted it to have some color, not just look like muddy dirt. I thought, “I’m going to look at this Hockney work and see what he was doing and why I like it so much.”

But I thought I would end up copying things that I don’t understand. He’s at the end of some journey that he’s taken. I don’t know what he’s thinking, what he’s solving, what he’s avoiding. I have my memory of it. I can say, “That impression is mine and mine alone. I didn’t steal that. Let me remember and go back to see about the picture in my head.”

Then, sure enough, it doesn’t look anything like David Hockney!

With books or artists that I like, I just get that small inspiration from it and then it is deliberate that I leave it alone. Your memories are much more useful than anything you could try to dissect from the work.

We appreciate the time you spent with us, Jon. We wish you well on your journey with your art and your writing.

Thank you! That means a lot that you guys honor this stuff.

For more on Jon Klassen:

Interview with Jon Klassen and Mac Barnett

Interview with Jon Klasssen: A Return Visit

I Want My Hat Back. © 2011 by Jon Klassen. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

This Is Not My Hat. © 2012 by Jon Klassen. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. Text © 2014 by Mac Barnett. Illustrations © 2014 by Jon Klassen. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.