An Interview with Carson Ellis

Carson Ellis

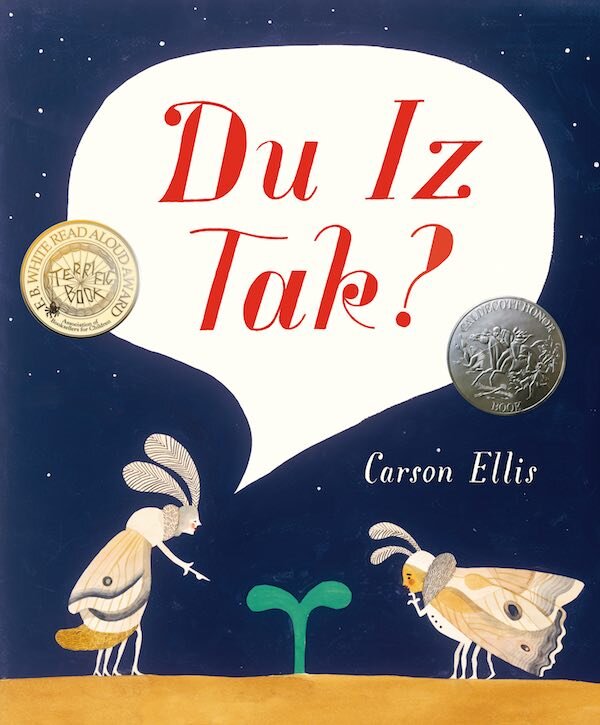

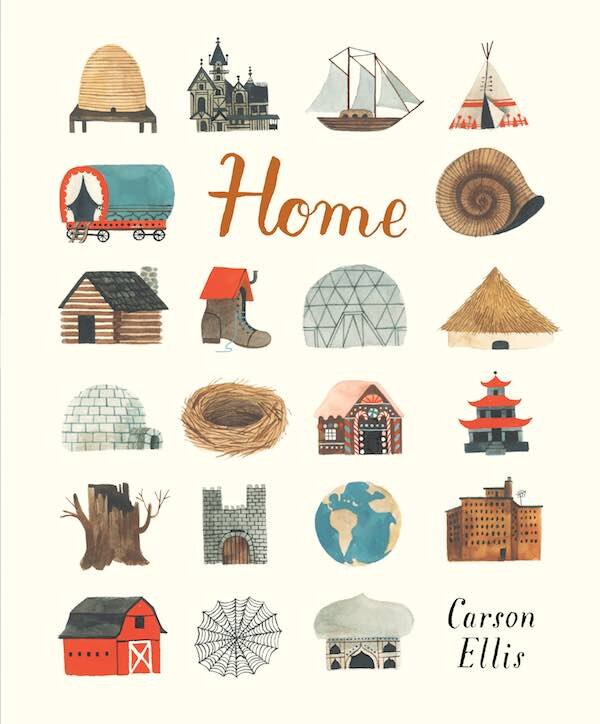

We interviewed Carson Ellis, award-winning illustrator and author of children's picture books, who is also an acclaimed fine artist. She has written and illustrated two best sellers, Home and Du Iz Tak?, a Caldecott Honor book, and a recipient of an E.B. White Read Aloud Award. She also illustrates her husband's (Colin Meloy) middle-grade novels; the most recent is The Whiz Mob and the Grenadine Kid and she is the artist-in-residence for his band The Decemberists. Carson lives and works in Oregon.

A Selection of Work

April 26, 2018

Since a picture book is often the first exposure to art for many children, we appreciate your commitment that the work deserves to be of the highest quality. Do you have some key points for aspiring illustrators or authors to keep them on that path?

I think illustrators and writers should do the best work they're capable of, regardless of their audience. That's obvious, I guess. But also nobody should feel compelled to dumb down their art for children. Don't subscribe to someone else's narrow view of what kids will and won't like, even if that person is your editor or art director. Don't let anyone tell you that book illustration should be colorful or joyous or silly. That's not always the case. That's not to say that it should be serious or dour either. Or that you shouldn't hear out the people you're working with if you don't agree with them. Or that all book ideas and illustration approaches have a place in children's literature. They don't. But, if in doubt, look around at the kid readers in your world and see what they respond to because it's often surprising. The only people who really know what kids like to read are kids.

Cover of Du Iz Tak?, Carson Ellis

Assuming you have had the opportunity to read Du Iz Tak? to kids in schools or on your book tours, what was their reaction to the text? Do they ask you to translate it for them? Do they come up with their own meaning? Have you learned anything unexpected about your book from these experiences?

When I read this book to groups of kids, I narrate it. I'll say something like, "Two damsel flies approach the plant and wonder about it. 'Du iz tak? asks the first damsel fly. 'Ma nazoot,' replies the other, shrugging." The narration is designed to gently hint at the meanings of some of the words. At various points in the reading, I'll translate words that might help them figure out what other words mean. I don't tell them what "du iz tak" means, but the phrase repeats throughout the book and on the last page, when a cricket wanders out into a field of little plants, points to one of them, and asks, "Du iz tak?" I ask my audience what they think that means and by then they typically know. (It means "What is that?") That's probably been the most unexpected and thrilling thing about reading that book to kids: that the language part actually works! They're able to figure it out.

Interior spread from Du Iz Tak?, Carson Ellis

Over time, as you have added color gouache to your ink drawings, do you find it has changed your approach to developing your illustrations?

Lately I do a lot more painting than drawing and, yeah, that feels like a much different approach. I'm thinking in terms of shapes and color and tone instead of line. I love drawing too but I feel like more of a painter these days. The art can be more atmospheric and I can create more immersive worlds with paint and that seems right for the kinds of books I've been illustrating. Though the art for the last book I worked on—The Whiz Mob and the Grenadine Kid—was all line drawings and that was a lot of fun. It was a nice break from gouache paintings which are laborious and I felt like it suited the book, which is set in France in the 60s.

Cover of The Whiz Mob and the Grenadine Kid, by Colin Meloy, illustration by Carson Ellis

Interior illustration by Carson Ellis from The Whiz Mob and the Grenadine Kid, by Colin Meloy

Cover of Wildwood, by Colin Meloy, illustration by Carson Ellis

Interior illustration by Carson Ellis from Wildwood, by Colin Meloy

You have a clear talent for writing that comes close to poetry. Do you still write any personal poetry? Are you working on a new picture book currently? Anything that you can share with our readers?

Thanks! I've written poetry since I was a teenager and I continue to but I don't show it to anyone. It's just for me. I don't have a writing practice or anything and I don't do it often. I just write a few poems a year. At any point in my life, including right now, I would tell you that the poems I've written in the past couple of years are great and all the earlier ones are lousy. Which means that in a couple of years I'll probably hate the poems that I like now. Which, I guess, is why I don't show them to anyone.

Interior spread from Home, Carson Ellis

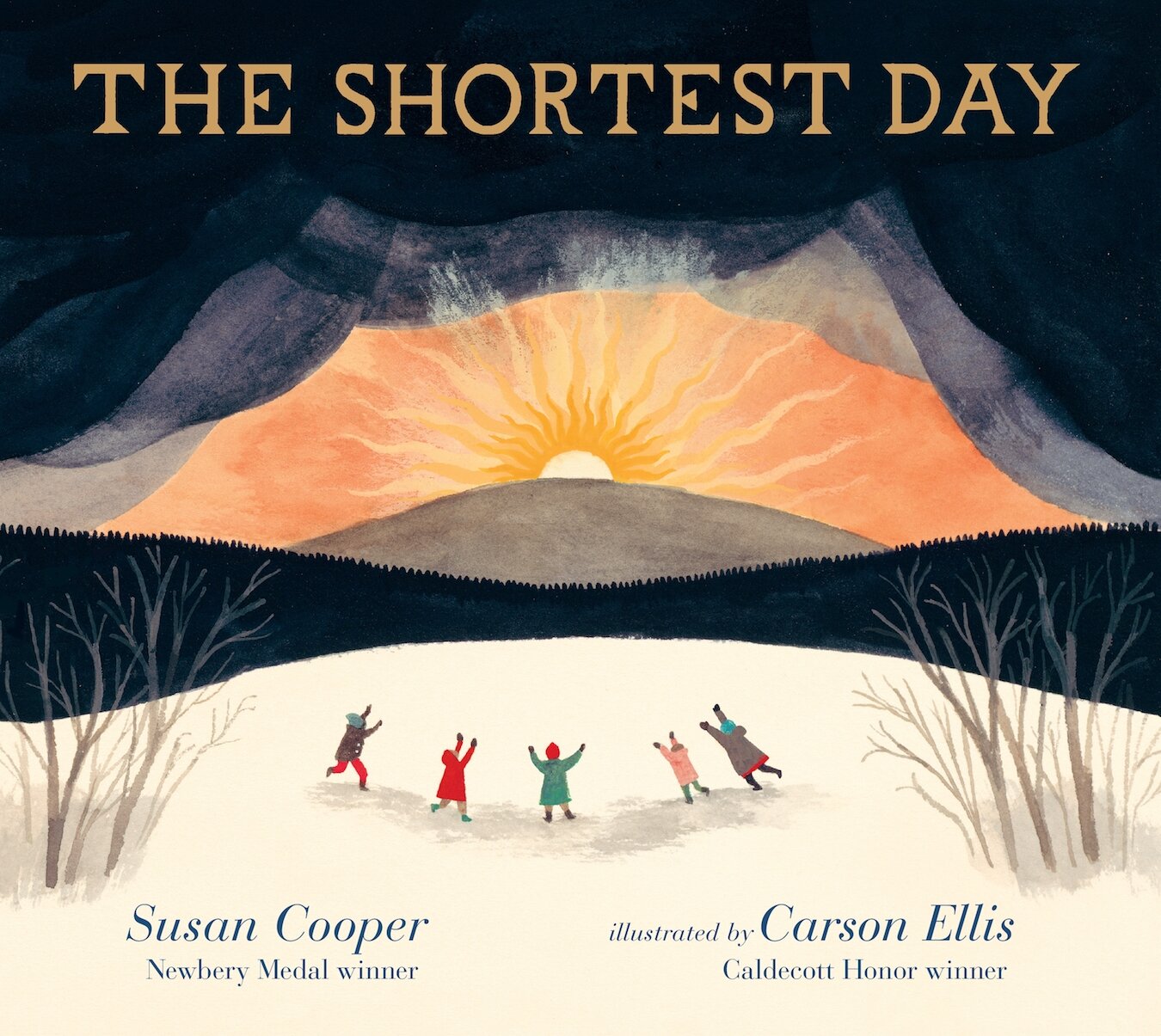

The picture book I'm working on right now is actually a poem. Not by me—by Susan Cooper. It's called The Shortest Day and it's about the winter solstice. It's been around for a while and is beloved by fans of Susan and of The Christmas Revels that she's involved with and wrote the poem for. So it's out there. You can Google it. It's very beautiful and mysterious and challenging to illustrate. Though now that I've got it figured out—I'm currently doing the finals—I love working on it. I'm not sure if I'm supposed to share art from it yet but here's a sketch:

A preliminary sketch from upcoming The Shortest Day, by Susan Cooper, illustration by Carson Ellis

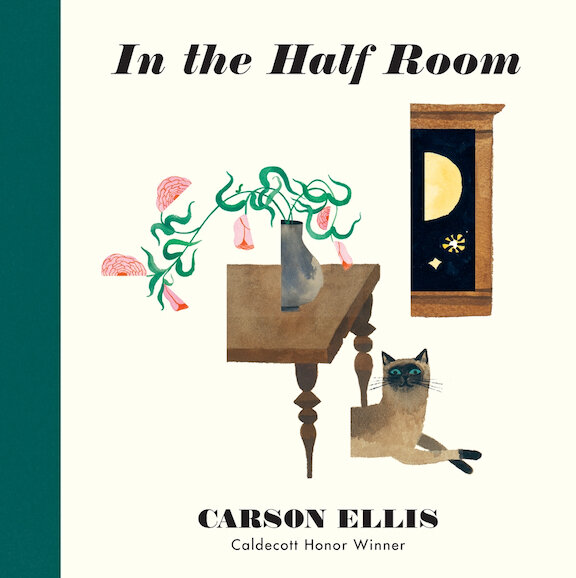

Other than that, I have another book I'm trying to write and I think it'll be longer and for older kids. But I'm still sorting it out. It's next on my docket.

Are there children's writers that you would like to work with? Or having written do you prefer to illustrate, write and create your own picture books?

Right now I'm more excited to work on my own books. But if a manuscript comes my way that I really love, I'll illustrate it. That was how I felt about The Shortest Day. I don't illustrate a lot of books by other authors these days unless they're my husband. But I read that Susan Cooper poem—it was sent to me by my editor as a picture book manuscript—and I fell under its weird spell. I felt like I had to illustrate it. I didn't even know who she was when I read the manuscript. When I told Colin, my husband, he was all, "OH MY GOD SUSAN COOPER." But I didn't know her books. Only that she had written this magical picture book manuscript.

Interior illustration from The Shortest Day, by Susan Cooper, illustration by Carson Ellis

In a previous interview, you preferred "mystical" over "whimsical" to describe your work. How do you distinguish and define these words?

I think of these words as opposites. To me, mystical means profound, sublime, indescribable, primeval, referring to some kind of deep inner-spirituality. Whimsical means quirky, precious, quaint, and honestly kind of empty. It's related to the word "whim". I get why people describe my art as whimsical. I can see it and I know it's mostly meant in a nice way; that it's fanciful and offbeat. So, I'm not saying that I don't make whimsical art, just that I'm trying to make art that is mystical.

Interior spread from Home, Carson Ellis

When you say that kids can "get it" is that because you feel we sometimes underestimate a child's ability to understand and appreciate a subject matter that is darker and more complex?

Yes, within reason. I don't think that all kids are ready to deal with whatever subject matter we want to lob at them obviously. My five-year-old is wild for horror. He loves scary stuff so I read him scary stories (I love horror too). But I won't read him Otto in the Tomi Ungerer anthology I just bought because it's about the Holocaust and we're Jewish and he's five. I don't think it's time for that conversation yet. For some other five-year-old and his mom it wouldn't be time for horror yet either. We're all different and we're entitled to set our own boundaries and make our own judgement calls. So it's probably too simple to say that kids "get it" and we should be exposing them to more difficult stuff. But, yes, I do think in general we tend to shelter them more than they want or need when it comes to books. I also think that in general we expect books for kids to have some kind of moral takeaway, some lesson to learn and I think that's a bummer. Books are art and when we make them for children they should reflect what makes literature and visual art wonderful to us, as adults. Of course some books should teach lessons. But some shouldn't.

The handwritten type in your books add to their style. Though not strictly calligraphic, the source is evident with your distinctive art. How did you come to that choice and do you anticipate always using your own hand-drawn type?

Yes, definitely. I've always loved lettering. My childhood sketchbooks are full of handwriting experiments and elaborate type treatments. My mom got me a calligraphy set when I was in middle school that I spent way too much time with. I have tons of books full of old alphabets and fonts that I draw inspiration from. It's been a thread that's run through everything I've done since the beginning. I love typography. I don't think hand-lettering has a place in every book though, and I've actually had to argue a lot for not using it.

Interior spread from Home, Carson Ellis

Not only do your books tell stories, you invite your readers to engage with the book by raising questions. Is this intentional?

Yes! Ideally reading picture books with kids should be a dynamic experience that everyone participates in. Books should raise questions and give us a chance to talk to each other and use our imaginations. That's not to say I haven't read the same Lego Ninjago book to my kid sixty times in a kind of robotic trance because I can't bring myself to care about it at all. There's a spectrum. But I love reading experiences on the other end of that spectrum, with books that inspire me to engage with them and with the person I'm reading to. That's the unique joy of picture books: reading them is social and I try to take advantage of that idea when I make them.

Interior spread from Du Iz Tak?, Carson Ellis

Your use of broad expanses of negative space on your layouts appeals to us. Does that graphic treatment come at the thumbnail stage or does it develop later in your process?

It's part of the idea from the beginning. One reason for all of that negative space is that I'm not great at backgrounds, I think because I'm not great at generalizing things. I want to labor over every detail. I also don't like making cluttered compositions. I want things to feel airy and spacious, not busy. I don't want elements of the composition to compete. It's just an aesthetic bent. Though the book I'm working on now is different because it's full of these sweeping, epic landscapes. I don't totally know how to paint them. In the past my approach to landscapes has been pretty stylized, but I wanted these to feel atmospheric and naturalistic. So there's very little white space. It's been hard! But I'm learning a lot.

The Picture Book Proclamation

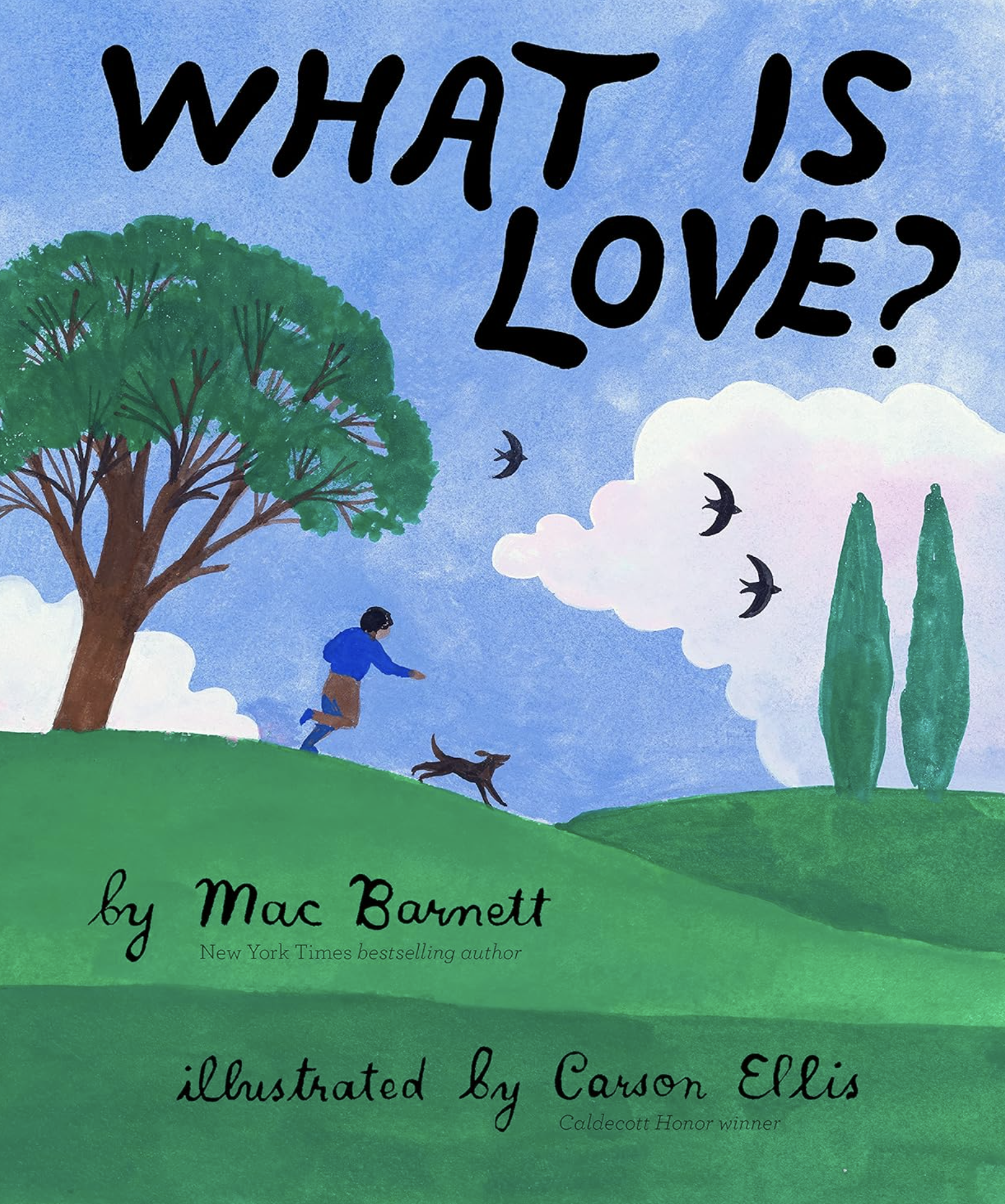

You created the illustration for the Picture Book Proclamation, which we featured in our interview with your friend and author Mac Barnett. We asked him the following question: Have you observed any changes that make you hopeful about the creation of children's books going forward? Carson, what are your thoughts on this?

I think I have observed changes in kids book publishing culture. When I started making picture books, I had this sense that so little was allowed. I came from the world of album art/fine art/editorial illustration and I was surprised by how chaste attitudes about kids publishing seemed. I was a picture book enthusiast before I started illustrating them. I'd been collecting them for years but the books I collected were older: from the 30s—80s. And the ones I loved felt weird and radical, even if they were wildly popular, like the books of Margaret Wise Brown or Outside Over There by Maurice Sendak. I remember thinking, when I started doing this almost 15 years ago, that nobody would publish Outside Over There today. Now I realize that there's a lot to unpack in that observation: that possibly nobody would have published it in 1981 either if it hadn't been written by Maurice Sendak. That, if Maurice Sendak had written Outside Over There 15 years ago, of course someone would have published it because he's Maurice Sendak. That when I made that observation I was younger, adjusting to my new job as a kids book illustrator, and feeling reactionary about the publishing culture, which felt prudish to me. So it's hard to tell how much has changed and how much I've changed. I used to think of my editors and art directors as The Man. Now I think of them as my friends and collaborators. Most of the time. So things have shifted. I do think, biases aside, that the picture book publishing climate in the middle part of the last century (during an all-out children's literature revolution spearheaded by the great Ursula Nordstrom) was brave, challenging, brilliant and avant in a way that we may never see again. But I see a lot of daring, absurd, wonderful, totally singular books being made now that maybe couldn't have been made 15 years ago. It gives me so much heart. Books like The Dark, School's First Day of School, Leave Me Alone, Sam & Dave Dig a Hole, They Say Blue by Jillian Tamaki, all of Jon Klassen's hat books—they feel very much in the spirit of Ursula's good books for bad children and I think the fact that they exist (and are so loved) bodes well for picture books. Especially for the kinds of books I like and want to make.

Cover of Outside Over There, Maurice Sendak

There is a show of your personal work at The Nationale Gallery in Portland, Oregon. We're interested in how your art supports and complements your illustration work for picture books.

Ideally I'd make a lot more personal work. It feels like an important part of what keeps me gratified as an artist. And it gives me the opportunity to experiment with mediums and approaches and whatever else. It's hard to evolve as an artist when you're working on a big project like a book because it requires continuity. Basically it requires you to not evolve. And I'm always working on a book. I've been kind of piecing together this balance of personal work and book illustration for years and it always feels tenuous and not-quite-right. I know, in my heart, that I'd be a better illustrator if I spent more time away from illustration, making whatever art I feel inspired to make. I've also been raising kids for the past 12 years, which makes it hard to take time away from my job that I love and that I struggle so hard to make time for, to make time for art that has nothing to do with my job. But I'm always drawing in a sketchbook when I can, especially when I'm traveling and can't work on book projects. That's what most of the art in that Nationale show was: drawings I made on book tours and family vacations. And right now I'm working on some embroidered stuff, what I hope will one day be a series of pieces for a show. Colin is on tour with his band for three weeks and for the past couple of nights, after I've gotten the kids to sleep, I've climbed into bed with this embroidery and worked on it in silence for an hour before I go to bed. Weird! But it's what I need at the end of the day, I guess.

Thank you, Carson, for sharing your work and your process with us.

For more on Carson Ellis:

All images used with permission from Carson Ellis, Candlewick Press and HarperCollins Children's Books.